Daniel Roseberry's Runaway Success on the Paris Runway

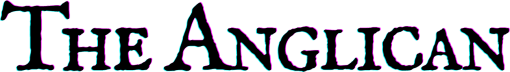

The Artist, His Art, and the Talent and Teacher Behind the Student

Superpowers

When our son Daniel Roseberry receives the International Designer of the Year Award from the Council of Fashion Designers of America this month, my wife and I will be there. Fran might remember the countless hours of patience and art instruction she provided him as a young child and budding artist. She has a strong artistic gift and comes from a family of artists.

However, though my mother was an amateur sculptor and surely sprinkled some of her DNA in our gene pool, I will think differently than my wife. She should stand up and take a bow, for sure. But as one with a stick-figure talent for illustration, I won’t remember anything I taught him in the realm of fashion, design, and aesthetics. Instead, when Daniel is presented with his well-deserved honor, I will think about his gifts and talents, where they come from, and what he and many others in my family are able to do, and I will conclude that they have what I do not have: Superpowers.

For skilled artists, Superpowers are as natural as breathing—regular and life-giving. They are a gift that is always available at a moment's notice. What seems natural to the endowed seems supernatural to me, a mere mortal. I can attest to the hours of training and practice of these talented people–gifts and talents are honed over thousands of hours of practice and patience–but the result appears magical.

To make this even more obvious, these art Superpowers are given freely to many members of my family: all my children, Fran’s mothers and brothers, and my mom.

And me? I watch. I write. Occasionally, I document stories from this colony of artsy people, and I do my best to match their wonders with my words.

Daniel’s Story

In Daniel, this Superpower has found its most dazzling expression. His ability to conceive images in his mind, translate them onto paper with an ordinary marker and a few well-placed and well-trained flicks of his wrist, and then transmute them into groundbreaking fashion has launched him to the top of his industry. Our family has always cheered him on, and this time will be no different: when he receives his award, all his siblings and their spouses will make the trek to the Big Apple to get in line, hug his neck, and celebrate his accolade. It’s a family affair.

Producing art at his level is a Superpower. Few achieve his renown or deserve to. His abilities stem from a natural aptitude, a nascent gift my wife and I recognized early in his life. But behind that innate talent is a lifetime of effort, training by his teachers and mentors (especially his mother), an abiding passion for the craft, and the grace of God.

For those not so gifted (alas, most of us), taking an image that only exists in one’s imagination or memory and then translating it into physical, tactile existence outside of oneself is one of the most marvelous abilities humans have. It is uncanny. It is spiritual, ineffable. It is hard to describe.

But I know the word for this mystery. I know how to speak about these acts of creation. Having been a church pastor, priest, and preacher for over forty years, I can tell you what this ability is. The finished product of real and tangible things which first existed in the ether of the mind is the definition of a sacrament. It’s an outward and visible manifestation representing an inward and spiritual reality.

Artists create sacraments.

The Signature of Man

The Catholic apologist G. K. Chesterton, in his masterpiece “The Everlasting Man,” says that art is the signature of man—of humanity—only humanity. No other creature has this ability or comes close to creating something outside of themselves to be used or merely admired. Who else but man can do such a thing?

Chesterton takes us to an imaginary cave to consider drawings on a wall etched some 12,000 years ago to prove the point. (Though his cave is imaginary, plenty of real-world examples exist.) And what do we see on that cave wall? We see drawings of animals, crude and stick-like. (I could draw them!) In cave after cave, we see drawings of bison, antelope, and other herd animals. These are drawings of animals. There are no drawings by animals.

Animals cannot draw. They never could. And they never will. Animals don’t make sacraments. They don’t do art.

No other creature can draw another creature or wants to. The cranky apologist even notes that the cave drawings had to come from the artist's memory because no herd could enter the cave. The cave artist drew what he remembered in his mind.

As only humans can.

Chesterton's insight about art aligns with a deeper, spiritual understanding of creativity. These crude drawings point to our unique place in God’s created order. (Now we are talking theology, a much more familiar turf for me.)

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, to be made in the image of God is to be like the Maker. We don’t believe that we look like God,or rather, who’s to know if we do? But we can say that to be made in the image of God is to be a maker, a creator. God, if we know Him for nothing else, is the Creator and we (of his image) are mini-creators. Or better yet, in some instances, we are co-creators. Our creative capacity, whether expressed in ancient cave paintings or modern haute couture fashion, stems from God's spirit within us.

Renowned author and Christian thinker Dorothy L. Sayers writes, "The characteristic common to God and man is…the desire and the ability to make things." She suggests that our capacity to create is not merely a talent or hobby but a reflection of our nature as beings made in God's image.

Indeed, when I watch Daniel sketch a design that will soon find its way onto a Paris runway or see Fran’s calligraphy transform a blank page into a perfectly proportioned and balanced frame, I'm reminded of this deep connection.

In this light, the artistic talents that are so pronounced in Daniel and which run through our family tree take on a deeper significance. They're not just skills or hobbies but expressions of something fundamental to our humanity. Our ability to imagine, create, and bring beauty into the world resides in us at the level of desire. Artists do this because they want to. And in Daniel’s case, Fran and I would agree that Daniel drew because he wanted to. But also because he had to.

From Childhood to Haute Couture

Daniel's artistic journey began remarkably early. At nine months old, during a house closing in March 1986, his small baby hand grasped a pen from my shirt pocket and started drawing on a manila folder. When we completed the real estate transaction, he had moved the simple first lines to curved arcs, connecting them to form footballs. Later, he added the laces. Looking back almost 40 years, it was a sign.

As a child, Daniel was insatiable in his pursuit of art. We would bring home reams of paper from a local print shop. He would mark page after page. Sometimes he would quickly scribble a few marks. On other sheets, he would move the pen, pencil, crayon, or marker slowly with greater care. Then, he’d flip the paper away and start again.

He was always hungry for more: more time, more paper, more markers, and more advice. He sought guidance from his mother like it was food, asking her to draw for him, teach him, and show her skill and technique.

His early subjects ranged from My Little Pony to high heels and Catwoman. He was particularly fascinated by the flowing lines and movement in the hairstyles of the Disney characters Pocahontas and Ariel from The Little Mermaid. (Look at Tarzan’s flowing locks in the image above.) These early influences would manifest in his fashion, where fluidity, swoops, and flair are crucial.

Daniel's artistic explorations were limitless. Once, he used a disposable coffee stir stick, blowing gently on one end, to move watercolor liquid over a sheet of paper. Without trying, he created a colorized portrait of Audrey Hepburn in a style reminiscent of his grandmother. Another time, he sculpted a plasticine clay figure of Pocahontas, proving his ability to translate his vision across different mediums.

Training Under Fran

The most consequential period in Daniel's development was the years his mother taught him everything she knew. Trained in art education and a skilled calligrapher, Fran became Daniel's primary art teacher, his first of many enduring fans, and one of his rare muses.

She bestowed her son with a handful of artistic principles that shaped Daniel's approach to design. She taught him about simple lines, except they aren’t that simple. A hacker like me draws a heavy line trying to outline a figure. An artist has a lighter touch, pulling the pencil off the page and setting it down in a different place where the line should go. The eye of the beholder fills in the blank. The void draws the viewer into the piece.

She also encouraged him to see mistakes and slips of the pen as potential design elements. She also taught him texture, pressure, and angles and encouraged him to draw anything he could see and everything he could imagine.

Daniel's artistic interests often clashed with his conservative Christian environment. While his Christian school provided him with a strong foundation in classics and humanities, it couldn't accommodate some of his more provocative artwork (Jessica Rabbit, for example). But Daniel was patient. Eager to explore his passion further, Daniel enrolled in a university life drawing course immediately after completing his sophomore year in high school.

From high school came college at the University of North Texas, but his first year was just a place-holder. Then came a year as a Christian missionary, followed by two years at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York City. In his second year at FIT, he was recruited to be an unpaid intern at Thom Browne. And the rest is history.

Daniel was discovered.

Thom Browne noticed the gift. He rapidly moved into the creative center of that small, exclusive brand, learned men’s suiting and production at the high end of retail. Then, he was assigned the task of creating a women’s line. Year by year, one theatrical fashion show after another, the brand grew.

TB started as a small shop in New York with a limited clientele but quickly had an outsized influence on the fashion world. It was the perfect training ground for him to learn everything about the world of high-end fashion. With Daniel as design director, the company exploded in growth and opened up boutiques and outlets worldwide.

He was with Thom Browne for ten years when he knew it was time to step away of his own accord. Fran and I had been to most of his fashion shows–in truth, she never missed one–but we knew that those days of high-end fashion were just the start of where our son would go. Daniel went into retreat mode, unsure of what might come next. He rented a small studio in Chinatown and rested from the ten-year marathon at Thom Browne. He waited. And he sketched. He breathed.

He could not have imagined what was coming next. None of us could.

His First Show in Paris

Daniel’s career took a surprise turn when he was invited to apply for the position of Creative Director at Schiaparelli, a storied brand that had been dormant for decades. As part of his application, Daniel used his retreat studio to sketch a visionary proposal. It was an impressive collection of drawings and ideas of styles, dresses, accessories, and elements that would, as it turned out, bring back the best of the past and develop a new path for the future.

I knew nothing about the Paris-based brand or the position. Fashion is so out of my league that I had nothing to offer and no advice to give except to express my complete confidence in his ability and judgment. I didn’t know what a huge decision the house's owner had to make, but after interviews and consultations, Daniel was appointed as the first American to lead a Paris Haute Couture House in generations. It was a big deal.

Just twelve weeks after his appointment, Daniel led his new team to open Fashion Week in Paris in July 2019. The show he conceived was not a typical runway march of the models up and back. His first show was theatrical brilliance, which took the fashion world by storm—and surprise. We were present for it, of course.

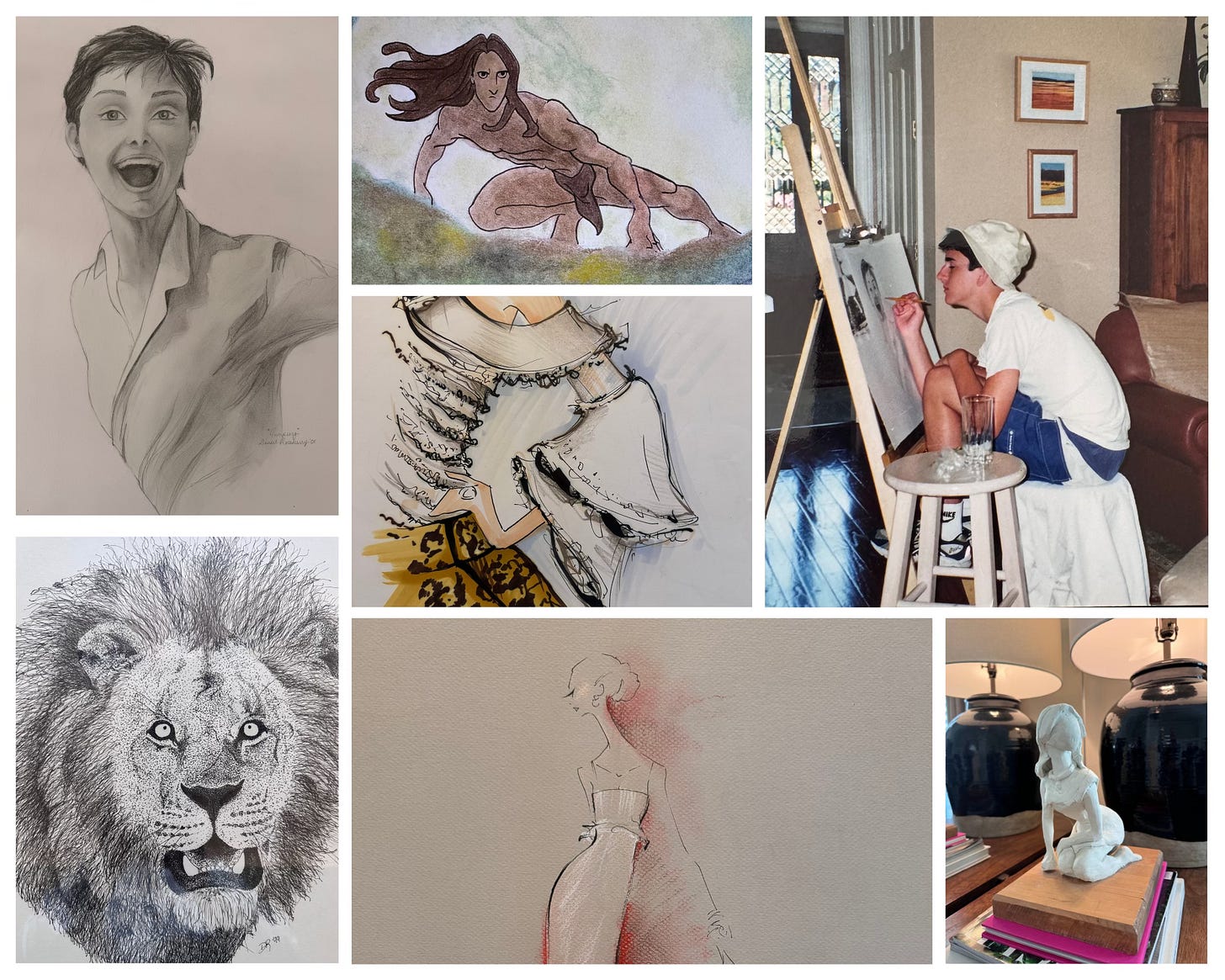

This show—his first show—was to recreate the time and place he spent drawing and developing his proposal to Schiaparelli. We heard the story later about this intense creative marathon: a retreat to New York's Chinatown, a rented studio under the loud trains of the subway, bulky Beats headphones to keep his ears warm in winter, a playlist from Spotify, stacks of paper, and his old-school pens and markers. That was his retreat.

Seven months after drawing the collection and barely four months after taking over as the new Creative Director, Daniel presented the Chinatown retreat on stage at his first show in Paris.

It was 10 AM on the first Monday of Fashion Week. Schiaparelli is always the first show scheduled. The venue filled up slowly.

The sounds of the New York trains filled the room. They were recorded to help set the stage and transport the Paris audience to Chinatown, into Daniel’s studio. It was as noisy as you’d expect a rented flat in Chinatown to be. Then, the spotlight flashed on and illuminated an artist’s table and a stool in the center of the stage.

Daniel walked in carrying his backpack. He wore jeans, white sneakers, and a denim shirt (now, his signature look). He approached the table and pulled his supplies from his backpack. The audience couldn’t have imagined what this was. Daniel was inviting us into his studio. Into himself. The recorded sound of the trains kept coming and fading, and the random noise of his home away from home, New York City, filled the room.

Then he sat at the art table, and when he slipped on his over-the-ear headphones, the noise of the traffic and trains ceased. We were now in Daniel’s head. He arranged his sheets of paper, took hold of his markers, the simple tools of his trade—and then magic happened.

Sketch and Release

Songs from his Spotify playlist filled the room as Daniel began to sketch. He created a sketch just as a model appeared on the runway. The in-house crowd could see Daniel drawing as the models entered the runway. He was drawing in real time. The online crowd could see it on a split screen: Daniel sketched the model's dress as she entered. It was brilliant!

As she walked, he drew. As he drew, she walked, crossing into a second spotlight. It was as if he was in the middle of the dress’s creation, and each model was freed from his mind and the pages of his sketchbook.

When one model had completed the circuit, the next one appeared and walked the runway. She, too, was sketched and released. It was a mesmerizing display of talent, timing, and confidence. Daniel was introducing himself to the fashion world—a world he had loved for decades. At the same time, he fully identified himself with each look. They were his. Everyone felt it.

My heart was in my throat.

Fran and I sat next to a distinguished-looking man. Before the show, he had ended a business phone call as people wandered in to take their seats. I heard the end of the conversation. He was an older man—my age, as it turns out— with white hair. I read his name on the seating card, telling me he was an editor of a fashion journal. He told his colleague, "Well, I'm here at Schiaparelli. I'm eager to see what this young man can do."

Thirty minutes later, with the show complete and my eyes wet with tears, I asked him, "Well, how do you think it went?" His summary would appear somewhere online later in the day. He said it was brilliant and impressive and mentioned something about a great career ahead. Then he asked if I knew the designer. I revealed myself, saying, "I'm his dad."

"Well, you must be very proud," Indeed I was.

The City of Light

Since his debut, Daniel has catapulted Schiaparelli into fashion's stratosphere. His designs, worn by luminaries known by first names alone - Gaga, Beyoncé, Kim, Celine, JLo, Michelle - have become a lingua franca of haute couture, speaking volumes on red carpets worldwide. Our boy from Plano is now a famous American in Paris.

We are now frequent pilgrims to Paris, a beautiful city I thought I would never know. But we are not Francophiles or tourists. We are parents of a talented and gifted man whose work has been noticed over and over again. Fran has a widening footprint, and deservedly so. As an extraordinary gift from a thankful son, Daniel organized a photo shoot of his mother in the recent haute couture collection. He took the camera in hand–he does much of his own photography–and shot half a dozen looks on her. It went viral. I loved that she was featured on the Schiap Instagram account between pics of JLo and Demi Moore. My wife: Paris fashion model.

A few months later, the photos were published in The Document Journal, along with a spectacular interview and a slightly edited transcribed interplay between mother and son. It was beautiful. When the journalist asked about the Christian faith that permeates our family, both Fran and Daniel were honest and lovingly true to their hearts and understanding. It was glorious for me to read.

Most recently, as I wrote from Paris in September, Fran has achieved some icon status. The paparazzi love her. She is happy to smile for them–she smiles for anyone! She loves people, and people love her too.

Faith and Fashion

And what about the Christian faith? People must wonder about this. Several have asked me about it. I am a Christian pastor and priest who led a large church in Texas for the majority of my ministry.

When I go to these fashion shows–I never want to miss even one–I wonder about these things too. Being at a show in Paris is about as far from a Texas church event as possible.

But in a sense, both are touching me at a similar point. Maybe others feel the way I think, too. When the people take their seats, the lights dim, and the music begins, I don't need to stretch my imagination to think we might be in a church. The place is packed with people looking for something that is true, lovely, and excellent. It's a secular echo of the Apostle Paul's exhortation in Philippians 4:8-9, urging us to dwell on what is true, honorable, just, pure, lovely, and praiseworthy.

Finally, whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is commendable, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things…and the God of peace will be with you. (Phil 4:8-9)

For me, this world of fashion and the church can be portals to a more beautiful reality, or the promise of it. There is something there for me, in both places, inviting me to contemplate the appeal and allure of beauty, especially in the coarse and ugly days of the past several decades.

Without ever referencing fashion in the pulpit, my preaching and teaching were a constant appeal to people to find beauty and meaning in the life and ministry of our Lord and the life he promises to those who follow him. The word that describes God in all of his glory is the same one I’d use to describe the incredible ensembles I see walk by me on the runway.

The world of fashion and the world of faith share a common word: Glorious

Conclusion

Daniel's impending receipt of the CFDA's International Designer of the Year award in October 2024 is a testament to his meteoric rise. Yet, for those who witnessed his early passion and prodigious talent—including, but not limited to, his mother and me—we would say we are not surprised. We are not shocked. To be recognized as the International Designer of the Year seems like the natural culmination of a lifelong journey. And we are thankful beyond words to be a part of it.

Daniel's Superpower ability to transform the intangible into the tangible and to bring forth beauty from the ether of imagination is remarkable. He has reached dazzling heights, changing the fashion world and bringing his visions to life on the grandest stages. Yet, as I watch him sketch or see his designs walk down a Paris runway, I'm reminded of that little boy feverishly drawing on reams of paper. The power was there all along, waiting to be honed, developed, blessed, and expressed.

In celebrating Daniel's success, I honor and thank God, the ultimate Creator, the source of all beauty and inspiration. Our son’s creative gift is a brilliant spark of the spirit that Chesterton recognized as uniquely gifted to humans by our Creator.

'O LORD, you are our Father; we are the clay, and you are our potter; we are all the work of your hand.' (Isaiah 64:8)

The Rev. David Roseberry, an ordained Anglican priest with over 40 years of pastoral experience, offers leadership services to pastors, churches, and Christian writers. He is an accomplished author whose books are available on Amazon. Rev. Roseberry is the Executive Director of LeaderWorks, where his work and resources can be found.

What a WONDERFUL story!!! (I had wondered if Daniel had attended FIT.)

So spot on with the Chesterton and DLS quotes!!! Sayers nails the essence of being in the image of God ... because when that is said in Genesis, God had only so far been shown doing one thing: creating!

My wife Cindy is currently reading GKC's The Everlasting Man to me aloud while I paint. For me, some of it is harder slogging than Sayers, because I know nothing of mythology.

"His early subjects ranged from My Little Pony to high heels and Catwoman."

It seems that (for example, if you check my Instagram page) I never graduated from the high heels and Catwoman phase, as a painter.

Amazing article! I love to read about artists!

David, i rejoice with you over the precious glorious gift God has given you and Fran in your son and his talent.