Earth to Earth. Ashes to Ashes. Dust to Dust. -- How A Learned Scholar with a Pastoral Heart Gave The World a Gift of Hope

Part Two: Thomas Cranmer’s Top Ten Prayers, Phrases, and Proclamations That Shape Our Faith

Prelude

In this summer series at The Anglican, I hope to read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest (as Cranmer himself once wrote) the well-known words of the English Reformer Thomas Cranmer. His five-hundred-year-old prayers and phrases still shape how English-speaking Christians speak, pray, marry, confess, and grieve. Many of his lines have entered the bloodstream of the Church—and even the broader culture:

The Collect for Purity (Communion Service)

To have and to hold… (Marriage)

We have erred and strayed… (General Confession)

Earth to earth, ashes to ashes… (Burial of the Dead)

The Comfortable Words (four Gospel sentences)

We are not worthy so much as to gather up the crumbs… (Prayer of Humble Access)

And on it goes.

Cranmer’s outstanding achievement—his magnum opus—was the Book of Common Prayer, that red or black thick treasure trove in your pew rack, or excerpted in your Sunday handout.

Among its most arresting sections is the Burial Office, a liturgy that faces the grave with sober honesty and unshakable hope. What Thomas Cranmer gave the Church was not just a funeral rite—it was a reformation of how Christians face death. He turned a fearful ritual into a faithful witness. With Scripture in our ears and resurrection on our lips, Cranmer taught us how to stand at the grave without despair.

In the next entry, we’ll examine the Burial Office's structure, flow, and force—how it speaks life in the face of death and why it continues to echo across centuries with undiminished power.

Earth to Earth. Ashes to Ashes. Dust to Dust.

The words are shocking. Spare. True. Obvious. And yet, they are filled with hope and wonder.

One of the things we must remember about Thomas Cranmer is that he was not just a theologian, liturgist, or statesman. He was a pastor, and the Book of Common Prayer is, through and through, a pastoral book.

Cranmer was writing for real people—commoners and kings alike—who knew the sting of death. In the 16th century, death was not abstract. It was not delayed. It did not happen far away in hospital wings or nursing homes. It happened at home, in the next room, in the very bed where someone had once been born. Children died. Women died in childbirth.

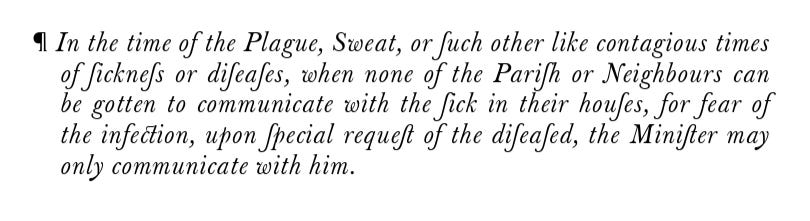

Plague swept through cities and left silence behind. In London, plague epidemics occurred in 1563, 1593, 1603, 1625, and 1636, significantly reducing the city's population. Here is a rubric from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer indicating the concerns families faced in their short lives:

Life was short, and everyone knew it.

Cranmer’s Burial Office is written in that key.

It is not sentimental. It is not evasive. It is honest, high-minded, and steeped in Scripture. And as one who has led hundreds of funerals over the years, I can say without hesitation: it is the most dignified liturgy the Church has ever given to the work of grief.

How it Begins

It begins with these earthshaking statements.

“I am the resurrection and the life,” saith the Lord…

“I know that my Redeemer lives…”

“Blessed are those then who die in the Lord, for they rest from their labors…”

These are not gentle thoughts. They are bold declarations meant to pierce the hush of sorrow. They interrupt death’s dominion with heaven’s voice. They don’t comfort us by pretending death is natural.

They comfort us by declaring death has been defeated.

Countless times I have been at a burial site—once even at sea, the Sea of Galilee—and there is no shortage of words. Cranmer gives us words that dare to sing at the grave.

“Yet even at the grave, we make our song: Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia.”

What other religion does that? What other funeral service gives such defiant joy, not in denial, but in deep, rooted confidence?

These words have shaped me. I have stood in cemeteries with wind on my face, tears on my stole, and mud on my shoes. I have stood beside teenagers taken too young, beside caskets too small, beside saints who were dear personal friends, who died full of years and faith. And every time, I have said it:

Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust…

There is no sentence more final.

But none more full of hope.

Three phrases. One truth: we are returning from whence we came. The earth. The soil. The dust.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Anglican to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.