How to Apologize: A Masterclass from the Annals of the Anglican Church

How Cranmer's Literary Masterpiece Shows the Way to Make a Sincere Apology to Someone You Care About

The Lost Art of Saying “I’m Sorry”

We hear them almost daily. A public apology offered by a celebrity, a politician, or a CEO. The tone is always the same: stiff, sometimes over-lawyered, and often emotionally distant.

“If you were offended…”

“My words didn’t reflect my values…”

”I might have gone too far…”

Two recent public feuds ended with apologies, but they’d have to be considered slightly underwhelming.

Elon Musk’s X-post admitted that his comments about the President “went too far.” But was that remorse or rebranding?

Simone Biles’ response wasn’t really an apology at all; one commentator suggested it had been crafted by lawyers and AI.

Of course, I can’t judge what’s in a person’s heart. Perhaps those public statements were followed by a phone call or a handwritten note. I hope so. I genuinely hope so. But my point is that you can smell a scripted “I’m sorry” a mile away. One part focus group. One part lawyer. One part publicist.

It’s not that we expect weeping or sackcloth, but sincerity would be nice. And clarity. And maybe a little humility.

My generation grew up with the great lie from “Love Story”, that love means never having to say you’re sorry. But we all know—married people especially—that love means having to say you’re sorry. A lot!

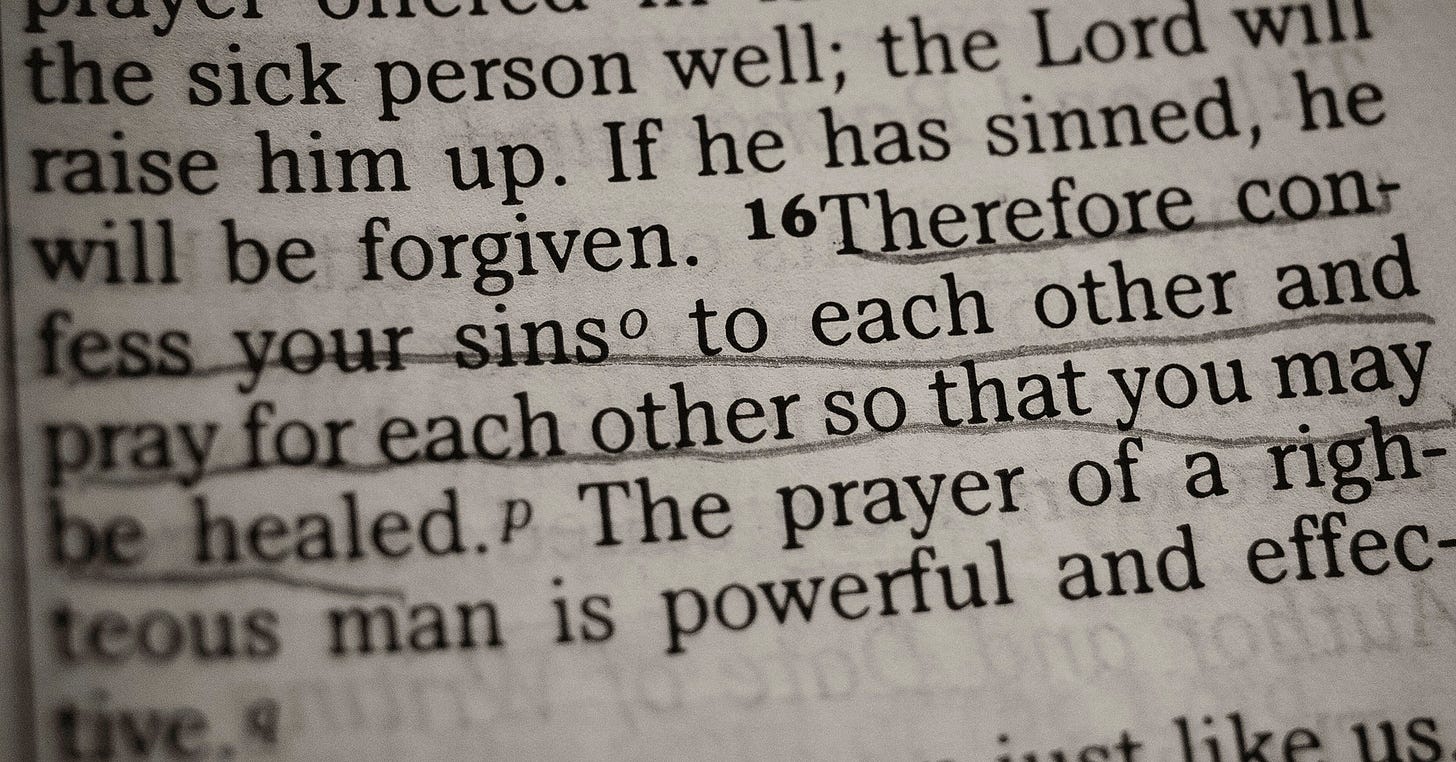

Which is why I’ve found myself returning to one of the greatest gifts of the Anglican tradition: Thomas Cranmer’s General Confession.

The General Confession of Thomas Cranmer

I’ve said it hundreds of times, led congregations through it, and memorized it by heart. But after nearly a decade away from regular liturgical leadership, I stood again at the altar—this time at St. Stephen’s in Hurst, Texas—and heard it with fresh ears.

When I read Cranmer’s nearly 500-year-old words, I was enthralled. And not for the first time.

Thomas Cranmer, the first Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury, was a reluctant revolutionary—bookish, pastoral, often politically cornered. He gave English Christianity not just a structure but a soul. In 1556, he was burned at the stake for his faith and convictions.

But his words outlive his flames.

Perhaps they have power because of his terrible end. But I think it’s more than that. His Confession is so spare, so exact, so unsparing that it teaches us how to say what we so often fumble: I was wrong, and I need mercy.

(Read the rest of this as a paid subscriber. I’ll show you Cranmer's perfect framework of making an apology in public or private and show you a case study in which a wife uses his framework to repair a broken relationship with her husband.)

The General Confession from the in Book of Common Prayer says the quiet part outlound. You know, the part we usually hem and haw and struggle to speak because it requires contrition, humility, trust, and faith, that is the part that the General Confession touches.

A few days ago, standing at the altar of that small Texas church as a short-term interim, I heard his words not as ritual, but as red-hot honesty.

We wouldn’t use the old prayer word-for-word in a personal apology. But its structure is helpful whenever we might find ourselves in hot water with someone we love. It names sin without spin. It confesses without compromise. One beautiful sentence follows the next, as the night the day.

Let’s read it slowly, the way it was meant to be heard:

The General Confession

Almighty and most merciful Father, we have erred and strayed from your ways like lost sheep. We have followed too much the devices and desires of our own hearts. We have offended against your holy laws. We have left undone those things which we ought to have done, and we have done those things which we ought not to have done; And apart from your grace, there is no health in us. O Lord, have mercy upon us. Spare all those who confess their faults. Restore all those who are penitent, according to your promises declared to all people in Christ Jesus our Lord. And grant, O most merciful Father, for his sake, that we may now live a godly, righteous, and sober life, to the glory of your holy Name. Amen.

Beautiful. Powerful. Perfectly worded. This is not a performance. It’s not a press release. It’s not reputation management. It’s the voice of a soul facing a holy God.

A Personal Framework for a Personal Apology

The General Confession follows a pattern worth recovering in daily life. We all know it is only a matter of time before we need to express our sorrow, make an apology, or confess a mistake, misdeed, or sin to another.

Let’s look at Cranmer’s flow for the next time we might need to know it. Here are the five elements of his framework. And as had been mentioned, they flow one from the other.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Anglican to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.