The Problem with Bishops. Part Two, Episode 1 - The Christ Church Stories

A Story of Leaving, Staying Faithful, and the Apostolic Anchor of the Church

This post begins Part Two of The Christ Church Stories. I’ll lay the foundation for what we did and why.

The Problem with Bishops

Every Anglican congregation has a bishop.

That’s not just a formality—it’s foundational. A congregation without a bishop is something, but it isn’t Anglican. Bishops, as the New Testament describes them, are episkopoi—“overseers.” Their hands may not be involved in the daily details of parish life, but their influence—spiritual, doctrinal, pastoral—is profound.

When a bishop is faithful, the church is guarded. When a bishop goes astray, the whole church feels the tremor.

Please support my work by taking out a premium subscription (for just $8 per month or $80 per year).

Let me remind you of the timeline:

In 1982, I was ordained a deacon in the Episcopal Church; a year later, in 1983, I was made a priest. One year after that, Fran and I and our two children relocated to North Dallas, where I served as the Assistant for Evangelism at Church of the Epiphany in Richardson. Then, in 1985, we moved to Plano to start a new church.

Christ Church began with a small group of 13 meeting on Friday nights in April 1985—forty years ago.

The city was booming, and families were moving in from across the country. There was an opportunity to build a church based on faithful worship, biblical preaching, and rooted community. Christ Church grew quickly, by God’s grace and through the hard work of many, and we became a self-sustaining parish within a year.

All Saints, Allen: From Boom to Bust

In the late 1980s, a man on our staff—someone closely connected to the bishop—felt called to plant a church in Allen, just north of Plano.

I believed in it 100%. He had joined our staff with the expressed purpose of planting a new congregation. All Saint’s transferred over a hundred people from our young church.

Robert Gibson and I were birds of a feather. He had served as a layman in the bishop’s parish in Florida and later became the Bishop’s Canon to the Ordinary. We were good friends. When our youngest child, Elizabeth, was born in 1987, Bob and Julie became her godparents.

The church in Allen grew wonderfully. But then, for reasons I can’t recall, Bob and Julie had to return to Florida. The diocese sent a replacement vicar—an unmarried woman in her forties with a progressive theology and a vision entirely unlike ours. She had no connection to Christ Church or our four foundational values: worship, preaching, lay ministry, and small groups. Nor did she want one.

She toed the standard Episcopal line of the day—a kind of liberal, inclusivist theology. In those years, it was often called a Rainbow something.

Over the next few months, the congregation dwindled to a few dozen. Eventually, the diocese closed All Saint’s.

Now, consider my position: I had supported a Christ Church-style church plant in Allen. Dozens from our congregation had left to help start it, which had grown to nearly 100 in attendance. Then, when the founding vicar left, the diocese installed a successor with a completely different ideology and theology and shuttered the doors within a year.

That was my first real sense that Christ Church was walking a different road than the Episcopal Church—and that my evangelical convictions would increasingly clash with the mainstream.

I could see clouds gathering. The Episcopal Church was changing and it wasn’t just a little. There were fundamental shifts in perspective and theology.

Lex Orandi, Lex Credendi, Lex Vivendi

There is a Latin maxim that captures the essence of the Church’s mission: Lex orandi, lex credendi. “The way we worship shapes what we believe.” Sometimes, it’s expanded to include lex vivendi—“how we live.”

Worship—that is, how we pray, reflects belief. Belief shapes life. And if you begin to change the words we use in worship—even subtly—you reshape doctrine and discipleship.

In other words, words matter. Words create worlds.

If we use trendy or imprecise words to describe sacred truths—even words for God—we end up with a diluted faith lacking clarity or conviction.

In the Episcopal Church of the 1980s, inclusive language trends were on the rise. “God the Father” became just “God.” Jesus Christ’s work and identity were redefined. Scripture’s authority was frequently questioned. Women were being ordained into what had always been a male clergy. And bishops began ordaining clergy who were openly and sexually active in same-sex relationships.

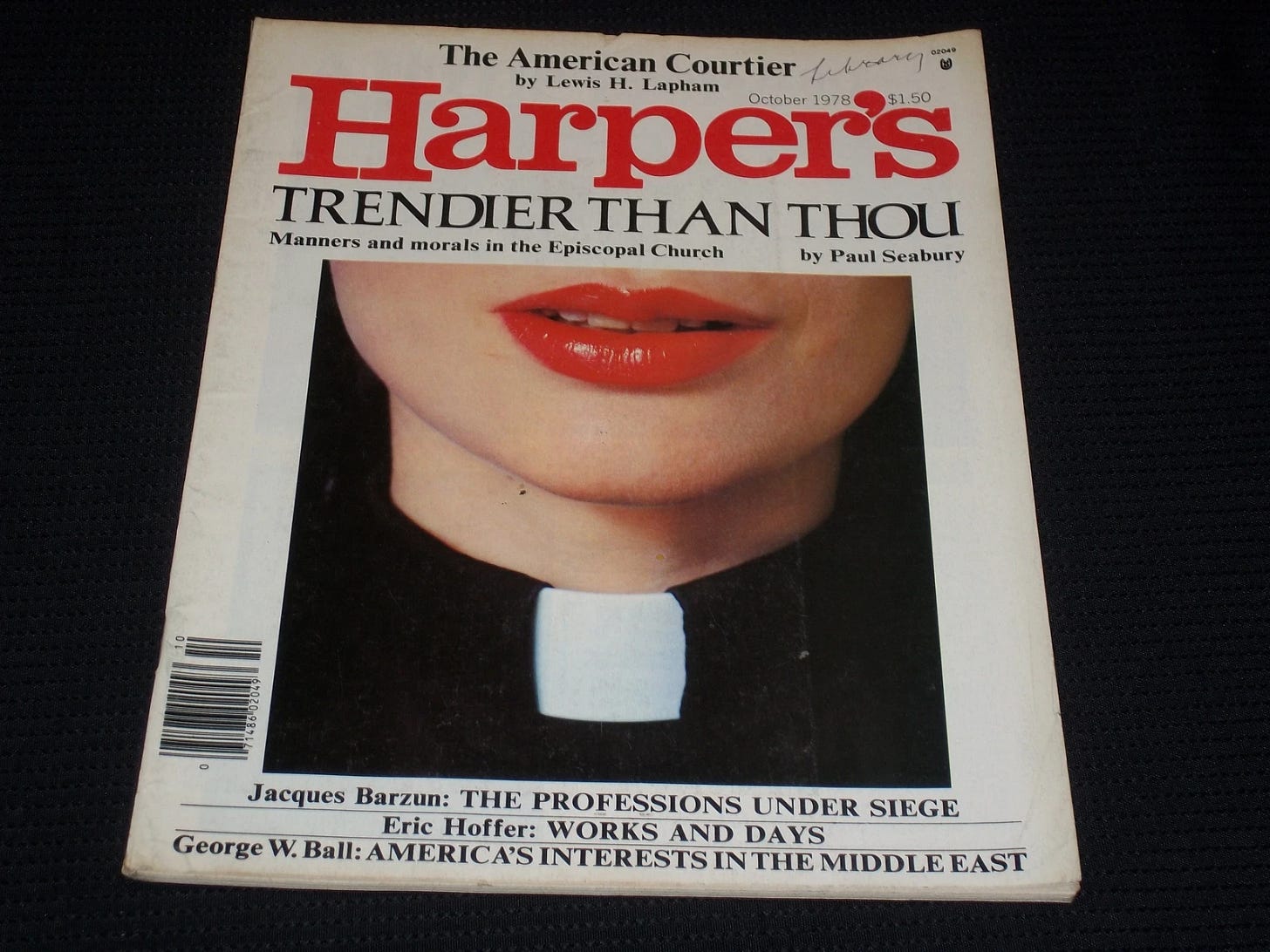

Paul Seabury’s article in 1979 was like throwing a cat in a bird cage of canaries. Read it all here.

Let me be clear: this was not only about language, women’s orders, or homosexuality. It was about the unraveling of biblical doctrine and the reshaping of the Church’s teaching by cultural winds.

And at the heart of it all was the office and role of the bishop.

And as I said earlier, if the bishop goes awry, the aftermath can wreak havoc.

What Bishops Do

Individual congregations can go off course. Pastors can preach poor sermons bordering on heresy. Some clergy may not believe the tenets of the Nicene Creed. They may doubt the Resurrection or question the Virgin Birth. Trends at the parish level come and go. But, to put it crassly, time and funerals have a way of purifying the Church, if the foundation holds steady.

But when bishops—those entrusted with guarding the faith—begin to promote false doctrine or ordain false-teaching leaders, the damage becomes systemic. The bishop’s impact can be generational.

What a bishop permits, blesses, or proclaims shapes the Church for decades.

That was precisely what was happening in the Episcopal Church.

The House of Bishops, charged with preserving the faith, unity, and discipline of the Church, had begun promoting teachings foreign to historic Christianity. Not every bishop, of course. But as a body, they failed to stop the tide.

Bishops Have One Job: Guardians

According to their consecration vows from the 1979 Book of Common Prayer, bishops are to guard the faith, unity, and discipline of the Church.

In the liturgy of consecration, the Presiding Bishop declares:

“You are called to guard the faith, unity, and discipline of the Church; to celebrate and to provide for the administration of the sacraments of the New Covenant; to ordain priests and deacons and to join in ordaining bishops; and to be in all things a faithful pastor and wholesome example for the entire flock of Christ.”

The bishop then pledges:

Q: Will you guard the faith, unity, and discipline of the Church?

A: I will, for the love of God.

Finally, the bishop is given a Bible and charged:

“Receive the Holy Scriptures. Feed the flock of Christ committed to your charge, guard and defend them in his truth, and be a faithful steward of his holy Word and Sacraments.”

One bishop once told me, “When a man becomes a bishop, he should never have an original thought again.”

He overstated the point, but it stuck with me. The job of a bishop is not to invent, but to preserve.

To teach what has been taught.

To preach what has been preached.

To believe what has been believed.

This is called the Vincentian Canon: to hold and defend that “which has been believed everywhere, always, and by all.”

But this was no longer the mindset of the Episcopal House of Bishops by the 1990s.

General Convention, 2003

In 2003, I served as an elected Deputy to the General Convention of the Episcopal Church in Minneapolis. That Convention voted to confirm Gene Robinson as bishop of New Hampshire—an openly gay man in a partnered relationship.

Elevating someone to the office of bishop who would never have been qualified in 2,000 years of Church history signaled that the Episcopal Church had left the historic faith.

As I said in a sermon at Christ Church, God doesn’t do new things. The last new thing He did was the Resurrection of Jesus Christ.

When the vote passed and the cheers erupted, I resigned as Deputy. I had to.

Quietly, I walked out to find my bishop and give him my pre-written letter. I did not want to make a fuss. I wasn’t seeking attention. But it was not to be.

Mark Anschutz, Rector of St. Michael’s in Dallas, rose to the microphone. He graciously acknowledged my resignation and called for unity. I hadn’t asked for any attention. I simply followed my conscience.

But outside the convention hall, the press was waiting. Reporters, cameras, microphones—all wanting a story.

They asked, “What are you doing? Why?”

All I said was:

“I cannot be a Deputy to this Convention because the Church has decided to leave the historic faith.”

That statement lit a match.

The Plano Conference

Within days, conservative leaders called for a gathering. They looked to Christ Church to host, and they counted on me to organize and emcee the entire event.

We organized a four-day solemn assembly: plenaries, workshops, communion services, Bible teaching, and prayer. Over 2,500 clergy and laypeople attended. The event was reverent and firm. We signed declarations and appealed to the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Thus, Christ Church became the lightning rod for this movement.

We were not trying to break away—we were trying to hold fast. Our appeal was to discipline the Episcopal Church, not to abandon it. But sadly, inevitably, this was the beginning of the breakup.

When we formally left the Episcopal Church in 2006, I did so with tears. It wasn’t triumph—it was necessity. We lost relationships, people, and funds. We were called schismatics.

But we left not because we had ceased to be Anglican, but because we still were.

Honey, I Shrunk the Church

The saga of the Episcopal Church, its decline over the last decades and its near collapse is a masterclass in how not to lead the Church of Jesus Christ. The last thing people are looking for in a church is a mirror of the society in which they live. People know the difference between standing for the faith of Christ who was crucified and bowing to the culture in which it stands.

For better or for worse, the Bishops did not stand for the Gospel. That is the power—and the peril—of the bishop’s office.

That’s why we need bishops who are faithful to Scripture, rooted in the apostolic witness, and courageous in their charge. When bishops stand firm, the Church is protected. When they falter, everything is at stake.

Next Time

You may ask: Why not go independent? Why not start a congregational church and move on?

Because we are Anglicans.

Anglican polity affirms that bishops are not optional. They are essential. From the Book of Acts to the Nicene Creed, bishops are the visible, apostolic link between Christ and His Church. They continue the work of the apostles—preaching the gospel, defending the faith, and ordaining new leaders.

Without bishops, we might still be a church. But we would no longer be Anglican.

That’s why we left.

Not to start something new. But to stay anchored in something very, very old.

But extricating a congregation from a diocese is not easy. There are no canons for that. The constitution does not conceive of it. But that is what we had to do. We had to stay Anglican but leave our parent denomination, the Episcopal Church.

That’s where we will pick up the story next on The Christ Church Stories.

If you’ve found these stories meaningful, would you consider becoming a Paid Subscriber to The Anglican? I’m keeping these stories free for everyone, but your support helps make that possible.

Think of The Anglican like church: it’s free to attend, but it needs faithful support to thrive. Consider the button below to be an offering plate.

Grace and peace,

David Roseberry

The Anglican is the Substack newsletter for LeaderWorks, where I share insights, encouragement, and practical tools for clergy and lay Christians. I’m also an author of over a dozen books available on Amazon.

If you are a Paid Subscriber, thank you! Thank you for supporting The Anglican and the ministry of LeaderWorks. If you are not a subscriber, please consider becoming one today.

Very sobering. Thank for this tone. The words, “I hadn’t asked for any attention. I simply followed my conscience,” were striking. It reminds me, too, of paying the price in my own life for acting on conscience. As you said, “I had to.” And the Lord stands by us.

Hi David,

There are many nuggets of wisdom in this piece. As an Anglican priest who laments about our bishop problem in the Australian Anglican church (with some very wonderful exceptions, including my own bishop who is a godly faithful man), I am very thankful for your ministry. BTW, I love what God is doing in regards to ACNA.