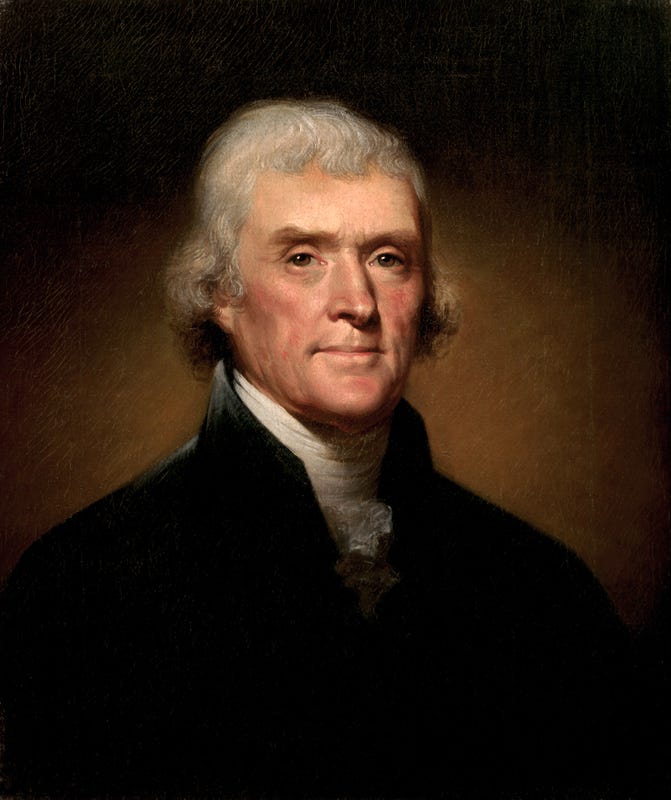

The Pursuit of Happiness: A Letter from Thomas Jefferson for the Fourth of July

What Jefferson meant—and what America has forgotten—about the signature phrase of our founding mind.

Every Independence Day, we recite the familiar promise of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” However, the word "happiness" has evolved since Mr. Jefferson first wrote it. This imagined letter offers his reflection—282 years after his birth—on what he meant, and why it matters more than ever.

July 4, 2025

To my fellow Americans,

I write to you now in the 282nd year since my birth, and nearly two and a half centuries since the Declaration of Independence was first adopted. Much has changed in our United States. You have grown in number, wealth, innovation, and influence. Well done!

And yet, I fear you have misunderstood one of the central phrases of our founding.

Permit me, then, to speak plainly about a word whose meaning has shifted most regrettably: happiness.

What We Mean by Happiness

When we declared that all men are “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights,” and named “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness” among them, we did not mean what many now seem to believe.

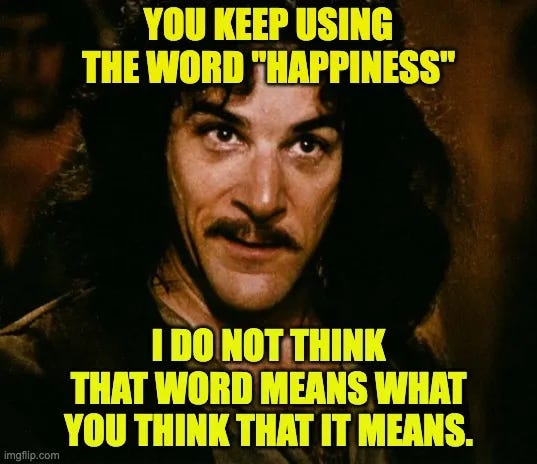

Today, when you hear happiness, you think of ease, entertainment, or personal gratification. However, in our day, we understood happiness to mean the flourishing of a virtuous life—a state the ancient Greeks referred to as eudaemonia.

This happiness is not a fleeting mood or a series of momentary pleasures. It is a condition of the soul. It comes from living in harmony with conscience, with reason, and with moral purpose.

Consider subscribing to The Anglican. Several times each week, I explore faith, culture, and the enduring wisdom of Scripture, tradition, and history—all for $8 per month or $80 per year. It's worth it!

The happiness we envisioned—indeed, the happiness my generation revered—was not found in indulgence, but in integrity. It was not a feeling so much as something formed by discipline, duty, and devotion to the good.

I did not invent this idea. I borrowed it, gladly and gratefully, from the ancients—Aristotle and Cicero—and the moderns—Locke, Hutcheson, and Blackstone. And yes, I admired the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, whose ethic of love, mercy, and virtue I believed to be the most sublime moral system ever devised.

You may not realize that I was not a classically Christian man.

I respected the Christian faith, but I was not religious in the modern sense of being devout or faithful. I found great delight in the moral teachings of Jesus, particularly in His call to love one’s neighbor, to live peaceably, and to do good. I once wrote to Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse that “the doctrines of Jesus are simple, and tend all to the happiness of man.” That is, they promote the moral health and harmony of the individual and the commonwealth alike.

But let it be clearly understood: the happiness I speak of—this eudaemonia—belongs not only to those of the Christian faith, but to any soul who longs to live with virtue, reason, and goodwill. It is a human pursuit, not a sectarian one. I commend it both to the faithful and the secular, to all who would build a life worth living.

My Sorrow. My Shame

I need to say this plainly: If I had paid closer attention to the Gospel itself—not just its moral lessons but the message that Christ died for all—I might have seen the people I enslaved for who they truly were.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Anglican to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.